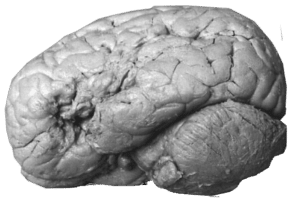

The birth of cognitive science. In 1861, "Mr Tan-Tan - His real name was Leborgne, and he died at Bicêtre Hospital. He got his nickname from aphasia, which prevented him from pronouncing anything other than this single syllable "tan" usually repeated twice in a row.

20 years later, Carl Wernicke performed a similar autopsy on the brain of a patient suffering from another form of aphasia, causing him to pronounce only sequences of words with no real meaning, such as "Boutique à manger rue on a copper candlestick or else.

ln found a large lesion in the posterior superior temporal gyrus, which he considered to be responsible for these language disorders - and which became known as Wernicke's area.

Cognitive science was born... in pain, let's face it.

We could also cite the misadventures of Phineas Gage, the American railway foreman whose head was partially smashed by a crowbar... and who survived, albeit with behavioural problems that Antonio Damasio will evoke in his book Descartes' error.

Each area of our brain corresponds to one or more functions: today, magnetic resonance imaging - or MRI - allows us to identify them in a less intrusive way.

All of you have already experienced the changing digicode number: for the first few days, you learn the new one by heart, and then you go back to the old one. "recite in your head before typing it when you get home in the evening. Then comes the moment when you act automatically...

And when we're asked for the code that some time ago we would have given immediately... we hesitate: we don't know it any more, we're forced to imagine standing in front of the door and typing it in!

Our memory is not unique: in fact, we have different forms of memory in different parts of our brain.

Semantic memory, for example, the memory of what we learn - at school, for example. "2 times 2 = 4 -Semantic memory is a declarative memory: when we are asked the question : "2 times 2?"the answer is " 4 ".

Procedural memory, on the other hand, is not declarative. "know" the keypad, but I "don't know say what I'm doing! Obviously I haven't forgotten the fateful number - otherwise I wouldn't be able to go home - but I'm no longer able to give it.

MRI studies showed that it was not the same area of the brain that was activated when we were learning or retrieving information - in other words, when we were using our semantic memory - as when we were performing an automatic action - linked to procedural memory: the data seemed to migrate from one part of the brain to another.

The obvious conclusion for marketing research is that there's no point in looking for information... where it doesn't exist! There's no point asking consumers to tell us what they do automatically: they can't - but we can observe them...

There are many other types of memory besides semantic and procedural memory: immediate, working, long-term, episodic memory too, memory of events and their context.

It's up to us to adapt our research tools to this diversity.